Larry Hurtado has posted his opinion of the Gnostics, that they were not intellectuals, but esoterics who taught a bunch of "mumble-gumble", such as a read of the Nag Hammadi texts reveal; that they were not engaged with reasonable arguments such as we find in the writings of the church fathers; and that pagans never engaged them, proving that they were not an important part of the intellectual scene. The only real intellectuals were the catholic Christians.

Now Larry is a good friend of mine - we have been members of the early high christology club since its inception, which is a good number of years. But that does not mean that we do not disagree, and on this topic we disagree. Larry is taking a standard position espoused by many biblical scholars (he is in very good company), that the Gnostics are non-consequential to Christianity and that their ideas and practices were irrational and secretive. Some biblical scholars would add to this description, perverse and exploitative.

I remember about ten years ago when I visited Oxford to work in the library, I was invited to dine at the table in one of the colleges. One of the biblical studies professors sat next to me and asked me what I was working on. When I told him the Gnostics and the Nag Hammadi texts, his immediate reaction was, "Why are you wasting your time on them? When I read the Nag Hammadi texts it was clear to me that it is all craziness. Nonsense. Go back to the New Testament where it matters."

So I have been working upstream most of my career, swimming against a current that is much stronger than I am. I guess I like the challenge, or I wouldn't keep doing it. I have spent a lot of time within the Nag Hammadi texts, reconstructing the worlds of the authors, which are not crazy once you learn their references and points of view. The Gnostics from antiquity were anything but crazy, inconsequential or irrational. But they were different. And difference often leads to misunderstanding.

So let's clear up some of the misunderstanding:

1. Basilides was a philosopher who converted to Christianity as a Gnostic. This was sometime between 110 and 120 CE. He wrote some of the first commentaries on New Testament texts, that is before they were part of any New Testament. He appears to have been our earliest biblical theologian. He was also a mathematician and astronomer.

2. Valentinus was a contemporary to Basilides. Tertullian, who dislikes him with a passion, admits that people at the time thought he was a "genuis" because of his command of the biblical materials and his exegetical abilities. He was also a poet. There was even a moment when some thought he would be the next bishop of Rome. When he was not elected, he felt a big mistake had been made so started his own church school to train Christians correctly.

3. We have a letter that Ptolemy writes to Flora (yes a woman convert) which is every bit a rational and reasonable interpretation of biblical texts that supports his view of the world as anything we have from the catholic Christians.

4. The Sethians participated in Plotinus' classes, much to his dismay. While he disagreed with them on several points, we are coming to find out that Plotinus and the Gnostics were in dialogue with each other and the influence of each other's philosophical doctrines went both ways.

5. Heracleon wrote one of the first, if not the first, commentary on the Gospel of John. Origen engages it thoroughly and from this engagement we can see that Heracleon was an astute philosopher and biblical theologian with very reasonable arguments for his positions.

6. Celsus engaged the Gnostics, although he called them Christians and knew of them only as Christians. It is because of his extensive engagement with these Christians that we know so much about a group that Origen calls the Ophians. Origen in fact is furious with Celsus, that Celsus thought the Ophians were Christians. Origen tries desperately to distance catholic Christianity from Celsus' description of (Ophian) Christianity. By the way, one of Celsus' arguments against them is that they were simply Platonists who had nothing new to say because Plato had said it already.

7. The Gnostics were engaged in actual debates with catholic Christians. For instance, Origen debated the Gnostic Christian Candidus in Athens. Archelaus debated Mani. This debate is recorded by Epiphanius and it is extremely learned and rational. We should also add here that there is a solid tradition that Simon and Peter debated, some of which is recorded in the Ps-Clem literature. Even if the records of these debates are not actual transcripts (they probably aren't), they do not portray the Gnostic opponents as irrational dunces. In fact, the Gnostics come across as very learned and articulate opponents.

What does this all mean?

1. The Gnostics were extremely rational and educated people. They were intellectuals and their study of biblical texts was as astute as (and sometimes they read the Greek better, as in John 8:44) the catholic Christians. They were engaged in a two-way debate with catholic Christians, a debate that was consequential to the birth of the catholic landscape, as well as the generation of a new form of spirituality: Gnostic spirituality.

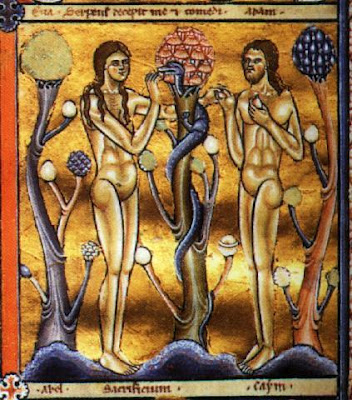

2. The Gnostics turned the tables on religion in antiquity. They really revolutionized conventional religion. While they based their world views on profound philosophical insights and reasoned biblical exegesis, they felt that reason could not get us all the way to God. Reason was step one. But step two was another matter. God, for the Gnostics, was beyond our comprehension, ineffable, unknowable by conventional means. The Gnostic felt that God had to be experienced. Ultimately it was the experience of God (which was had through intense ritual events) that mattered. This was the pinnacle of knowledge. This was step two, and it is what they thought other Jews and Christians missed. The Gnostics felt that other Jews and Christians had mistaken lower gods for the real God who was beyond all the images and forms we can make of him-her.

3. The consequence of their form of religiosity was enormous, as I am writing about now in

The Ancient New Age

,

where I argue that Gnostic spirituality which emerged in antiquity has

won the day and now forms the basis of modern American religion. The book will be published with Columbia University Press.

I go now to keep writing my chapter on Gnostic ritual: "Helltreks and Skywalks"...