What is the Gospel of Thomas?

The Gospel of Thomas is...

April DeConick studying the Gospel of Thomas in the Coptic Museum, Cairo, 2005

The Gospel of Thomas is one of the Nag Hammadi texts. It is a "living book" featuring the voice of the "living Jesus." It is a written gospel that developed over half a century within a church environment dominated by oral consciousness and gospel performance. The Gospel of Thomas began as a smaller gospel of Jesus' sayings, organized as a speech handbook to aid the memory of preachers. I call the earliest version of the Gospel of Thomas, the Kernel Thomas. The Kernel Thomas originated from the mission of the Jerusalem Church between the years 30-50 CE. It was taken to Edessa where it was used by the Syrian Christians as a storage site for words of Jesus. Its main use in the Syrian Church was instructional. The Kernel sayings were subjected to oral reperformances, which was the main way that the text was enhanced with additional sayings and interpretations. Later sayings accrued in the Kernel gradually as the gospel moved in and out of oral and written formats. The Gospel of Thomas can be read as a document that reflects shifts in the consistuency of its caretakers (from Jew to Gentile) and its theology (from apocalyptic to mystical). The Gospel came into its present form around the year 120 CE.

In its final form it is both encratic and mystical, the result of the interiorization of the apocalypse in face of its failure to materialize according to the earlier expectations of the Syrian Christians. The encratism and mysticism in this text developed in tandem with Alexandrian Christianity, probably the result of exchange of ideas and texts that took place along the trade routes and roads from Edessa to Alexandria. The adaptation of this Gospel from 50 to 120 CE did not occur as a conscious program to alter the sayings of Jesus, but was the result of shifts in communal memory as past recollections of the group were updated and renewed in and for the group's present.

The following publications address my work on the Gospel of Thomas

The Gospel of Thomas

"Human Memory and the Sayings of Jesus: Contemporary Experimental Exercises in the Transmission of Jesus Traditions"

2008. “Human Memory and the Sayings of Jesus: Contemporary Experimental Exercises in the Transmission of Jesus Traditions.” Pages 135-180 in Jesus, the Voice, and the Text: Beyond The Oral and the Written Gospel. Edited by T. Thatcher. Waco: Baylor University Press.

“Mysticism and the Gospel of Thomas”

2008. “Mysticism in the Gospel of Thomas.” Pages 206-221 in Das Thomasevangelium: Entstehung-Rezeption-Theologie. Edited by Jörg Frey, et al. BZNW 157. Berlin: DeGruyter.

Abstract: This article summarizes DeConick's position on the esotericism in the Gospel of Thomas as representative of an early form of Christian mysticism growing in Syrian soil. It was a mysticism of a "paradise now," an internalization of the apocalypse that recreated Eden within the parameters of the Church, including the transformation of the faithful into Adam and Eve as they were before the Fall. This situation was opportune to develop a mysticism of vision and heavenly journey, a mysticism that represents a precursor to later Eastern Orthodoxy.

“The Gospel of Thomas”

2008. “The Gospel of Thomas.” Pages 13-29 in The Non-Canonical Gospels. Edited by P. Foster London: T&T Clark. Reprint from Expository Times 118 (2007) pages 469-479.

Abstract: This article views the Gospel of Thomas as the product of an early Eastern form of Christianity, most probably originating in a Syrian context. The text should not be seen as representing some Gnostic or marginal sapiential form of Christianity, rather it reflects a trajectory in ‘orthodox’ Christianity that valued mystical or esoteric teaching. Such traditions have been found in mainstream Christianity throughout its history. The text of the Gospel of Thomas is understood to be a rolling corpus, or aggregate of sayings that represent different moments in the life and history of the early Thomasine community.

“Corrections to the Critical Reading of the Gospel of Thomas”

2006. “Corrections to the Critical Reading of the Gospel of Thomas.” Pages 201-208 in Vigiliae Christianae 60.

Abstract: This article offers suggestions for corrections to the critical reading of several passages in the Gospel of Thomas. The passages discussed are P.Oxy. 1.24; P.Oxy. 654.8-9; P.Oxy. 654.9; P.Oxy. 654.15; P.Oxy. 654.25; P.Oxy. 654.26-27; NHC II,2,39.34.

“On the Brink of the Apocalypse: A Preliminary Examination of the Earliest Speeches in the Gospel of Thomas”

2005. “On the Brink of the Apocalypse: A Preliminary Examination of the Earliest Speeches in the Gospel of Thomas.” Pages 93-118 in Thomasine Traditions in Antiquity: The Social and Cultural World of the Gospel of Thomas. Edited by J. Asgeirsson, A.D. DeConick, and R. Uro. Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies 59. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Abstract: This paper is a preliminary look at the Kernel Gospel through the lens of rhetorical analysis. DeConick examines the five speeches of Jesus in the Kernel Gospel of Thomas, and concludes that Jesus' message at this early stage of interpretation had an apocalyptic character, featuring eschatological dimensions as well as mystical ones. These mystical ideas, however, took on a life of their own when, after the fall of the Jerusalem Temple, the Thomasine Christians felt the impact of the delayed Eschaton. With the collapse of their teleology came a reformation of their apocalyptic thought. This reformation resulted in a shift that served to isolate the mystical dimension from the temporal, making the mystical an end unto itself.

“Reading the Gospel of Thomas as a Repository of Communal Memory”

2005. “Reading the Gospel of Thomas as a Repository of Communal Memory.” Pages 207-220 in Memory, Tradition, and Text: Uses of the Past in Early Christianity. Edited by A. Kirk and T. Thatcher. Semeia 52. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

Abstract: Reading the Gospel of Thomas as a repository of early Christian communal memory suggests that the Gospel contains traditions and references to hermeneutics that serve to reconfigure older traditions and hermeneutics no longer relevant to the experience of the community. In the case of the Gospel of Thomas, the community's original eschatological expectations were disconfirmed by its contemporary experience of the non-Event. When the Kingdom did not come, rather than discarding their Gospel and closing the door of their Church, the Thomasine Christians responded by reinterpreting Jesus' sayings, believing themselves to have previously misunderstood Jesus' intent - to have applied the wrong hermeneutic to his words. So they aligned their old traditions with their present experience, rationalizing the non-Event, shifting their theology to the encratic and mystical, and creating a new hermeneutic through which the old traditions could be viewed. This response is visible in the way in which they revised their Gospel, adding question-and-answer unites and dialogues that addressed the subject specifically, along with a series of new sayings that worked to instruct the believer in the new theology and guide him or her hermeneutically through the Gospel.

"The Original Gospel of Thomas"

2002. “The Original Gospel of Thomas.” Pages 167-199 in Vigiliae Christianae.

Abstract: This is the article that started it all, and ended with the publication of Recovering the Original Gospel of Thomas. In this piece, DeConick begins to explore the possibility of the rolling corpus as a model for Thomas' compositional history. She starts to lay out her reasoning and her methodology, although this does not become fully developed for her until she writes Recovering, especially in terms of the importance of orality.

"Stripped Before God: A New Interpretation ofLogion37inthe GospelofThomas"

1991. Co‑AuthoredwithJarlFossum. “Stripped before God: A New Interpretation ofLogion37inthe GospelofThomas.” Pages 123-150 in Vigiliae Christianae 45.

Abstract: This article challenges the long-held tradition started by Jonathan Z. Smith, that saying 37 is baptismal. Through comparative analysis, DeConick and Fossum suggest that the actual ritual alluded to may be unction.

1990. “TheYokeSayingintheGospelofThomas 90.” Pages 280-294 in Vigiliae Christianae44.

Abstract: This is a form-critical investigation of saying 90 and its Matthean parallel. DeConick concludes that the version preserved in the Gospel of Thomas is earlier than that preserved in Matthew.

Frequently asked questions...

April DeConick visiting the Giza Pyramids, Cairo, 2005

Where did the Gospel of Thomas come from?

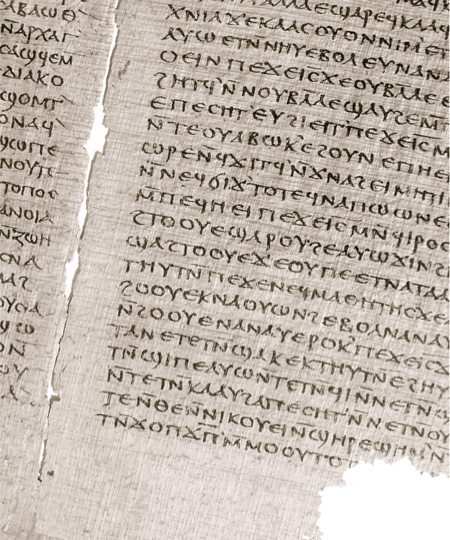

We have known about the existence of an early Christian gospel named the Gospel of Thomas since the early third century because it is mentioned by Hippolytus, who even quotes an elaborate recension of saying 4. In the late 1800s, Professors Grenfell and Hunt dug up a hoard of papyri in Oxyrhyncus, Egypt. Three of these Greek papyri fragments are pages of the Gospel of Thomas, although their identification as such was not made certain until the 1950s when a full Coptic version was noticed among another papyri find from 1945 near Nag Hammadi, Egypt. This latter find was a cache of leather bound books - we have twelve of the books and part of the thirteenth - and these are housed today in Old Cairo at the beautiful Coptic Museum. The three Oxyrhynchus fragments are housed today at Harvard, Oxford, and British Library.

How does the Gospel of Thomas compare to the New Testament gospels?

The Gospel of Thomas is quite different from the New Testament gospels in that it is a gospel of sayings of Jesus. Most sayings are introduced with the simple attribution "Jesus said," one listed after the other. Narrative is practically absent from the Gospel of Thomas, at least in terms of the type of narrative details and elaborate settings for the sayings that we find in the New Testament gospels. In this way, the Gospel of Thomas is closer in genre to the reconstructed Q, the synoptic sayings source that has been postulated as a major literary source for Matthew and Luke. The Gospel of Thomas is not Q, but it does represent the type of gospel that Q might have been.

There are a number of sayings of Jesus that we find in the synoptic gospels that have parallels (although in different recensions) in the Gospel of Thomas. There are several sayings in Thomas that have parallels in John, but on the level of thematic allusions rather than direct recensions. And there are a number of sayings in the Gospel of Thomas that are unique, unparalleled in the New Testament gospels.

What is Thomas' relationship to the New Testament Gospels?

Since the discovery and translation of the Gospel of Thomas in the 1950s, scholars have mainly been in two camps on this. Either they argue that Thomas is a gospel that was based on the New Testament gospels and "perverted" the sayings to meet some heretical theological agenda, or they argue that Thomas is a gospel that was independent from the New Testament gospels and preserved sayings of Jesus from an early Jewish Christian literary source or from early oral tradition. There are good (and bad) arguments for both cases, and essentially the field is at a stalemate on the question.

My own work is trying to get us past this, to think about it in different terms. If the Gospel of Thomas is a text that was very old and grew over time, then we probably have a complicated relationship to the New Testament gospels. On the one hand we would expect some of the sayings in the Gospel of Thomas to represent early independent traditions, before the Synoptics were even written. But as the Gospel of Thomas was adapted over time, its sayings naturally would be adjusted to the knowledge of other texts and to the memory of other texts. Add to this the fact that scribes when copying and translating texts into new languages felt quite free to alter the wording to fit more precisely their knowledge and memory of other texts, and we have a very complex situation of secondary orality and scribal adaptation. By the way, we find all of these operational in the Gospel of Thomas I think.

So what this means is that arguments for dependence aren't going to cut it anymore. We have before us the difficult task of figuring out what type of dependence we are talking about, alongside the acknowledgment that dependence in our late document does not necessarily mean dependence of the original Gospel of Thomas on the Synoptics.

Is the Gospel of Thomas Gnostic?

The quick answer to this is "no." The spirituality in this gospel has been misunderstood and mislabeled from the very beginning of its interpretative history. The reason for this has to do with the fact that until the Nag Hammadi texts were found, we didn't know what Gnostic really was. Scholars tended to apply it very loosely to any text or tradition that they believed to be dualistic and anti-world or body, which expressed the opinion that within the human being was "light" redeemable through gnosis or knowledge. After studying the Nag Hammadi texts for fifty years, we now realize that this is a nonsense definition because it is so broad as to be useless. Instead we have come to realize that Gnostic spirituality is marked by a distinctive set of features including direct contact with a transcendent God through specific ritual practices, an innate spirit that is consubstantial with God, a transgressive attitude toward established religions and their scriptures, and seeker orientation that was very inclusive, spanning a variety of philosophies and religions in antiquity.

The spirituality in the Gospel of Thomas is a form of early Christian mysticism. It was a contemplative type of Christianity that grew in Syria as well as Alexandria. The idea was that each person had the choice to grow into God's Image or to remain stunted due to Adam's decision. If the person chose to grow, then the divinization process was gradual and included not only ritual activities like baptism and eucharist, but also instructional and contemplative activities. Part of the process then was living as Jesus lived - it was imitative. The other part was contemplating who and where Jesus was. This contemplative life led to heavenly (or interiorized) journeys and visions of God. Eventually the faithful would become like Jesus, replacing their fallen image with the image of God. This contemplative Christianity is not heretical, but an early form of eastern orthodoxy!

April DeConick writing at Illinois Wesleyan University 2004

Why wasn't the Gospel of Thomas included in the New Testament?

The process of the canonization of the New Testament was long and involved. It took almost four hundred years. The date we traditionally give to its closure is 367 CE, when Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria records the books in the NT as being those we have in it today. There are many reasons for Thomas' exclusion, not the least among them political - it was a text that in the third century was used by the Naassene Gnostics (who rewrote it for their own purposes) and the Manichaean Gnostics (who used it liberally in their liturgies). Once a text began to be used by a heretical group, it became suspicious, especially if this happened in the third or fourth centuries. Texts included had to have:

- apostolic connections - something Thomas had

- be used in liturgy across the Mediterranean world - which Thomas wasn't, since it was a distinctive Syrian text with some distribution in Egypt

- predate 150 CE - which Thomas did

- support the theology of the framers of the canon - which Thomas didn't, since it was anti-marriage and pro-mysticism or "revelatory"

What does the Gospel of Thomas tell us about Jesus?

Given its use by at least two heretical groups in the third century, its emphasis on seeking new revelation, its stance against marriage and procreation, and its limited distribution and use in liturgy, it didn't have a chance to become part of the New Testament.

This gospel understands Jesus to be a charismatic figure. By this I mean, Jesus continues to live in their community even after he has died. His spirit continues to speak to this community of faithful, and they continue to record his teachings. They do not appear to have made any distinction between the "historical" Jesus before death and the "spirit" Jesus after death, at least in terms of authority or historicity of his words. The Jesus that emerges in the Gospel of Thomas is not entirely foreign to the New Testament portrayals, particularly as we see him emerge in the Gospel of John - but also, as we see him in Mark, teaching publicly to the crowds and privately his mysteries to a few close followers. His message is either similar to the New Testament Jesus, or contiguous with him. He teaches against carnality and succumbing to bodily desire. He's an advocate for celibacy. He preaches that the Kingdom of God is here, that people must make a choice whether to enter it or not, that this choice requires an exclusive commitment to him and God, that the going is tough and few will be able to make it. He demands a lifestyle of righteous living, promises rewards including personal transformation and revelation.