John's Gospel and Intimations of Apocalyptic, edited by Catrin Williams and Christopher Rowland

/In July, four years ago (wow has it been that long ago?) a number of us met at Bangor University to discuss new directions in research on the Gospel of John and apocalypticism. The conference was in response to John Aston's book Understanding the Fourth Gospel, and the fact that the apocalyptic dimensions had not received the kind of study that Aston suggested would be valuable. How is the text pervaded with themes concerning the apocalyptic or revelation? How does the Johannine narrative offer intimations of another world, another reality, without a direct theophany typical of so many apocalypses (p. ix)?

I dealt with centuries of mistranslations of John 8:44 and argue in my contribution to this book that this text reveals a long-kept secret that the early Johannine community believed that the devil had a Father who is the Jewish biblical god. This god is not Jesus' Father. "Why are the Heavens Closed? The Johannine Revelation of the Father in the Catholic-Gnostic Debate." I also examine 1 John and show that this letter is written to domesticate the early community's original understanding of John 8:44. This understanding of the Gospel of John forms now the basis of my understanding of Johannine Christianity, and will resurface in my chapter on the fourth gospel (John and the Dark Cosmos) in my book The Ancient New Age.

If you are interested in the Gospel of John and its intersection with revelation, this volume contains some really "new" ideas and I highly recommend it.

Authors and Table of Contents:

- Christopher Rowland and Catrin Williams, Introduction

- John Ashton, Intimations of Apocalyptic: Looking Back and Looking Forward

- Benjamin Reynolds, John and the Jewish Apocalypses: Rethinking the Genre of John's Gospel

- Ian Boxall, From the Apocalypse of John to the Johannine "Apocalypse in Reverse": Intimations of Apocalyptic and the Quest for a Relationship

- Jörg Frey, God's Dwelling on Earth: 'Shekhina-Theology' in Revelation 21 and in the Gospel of John

- Catrin Williams, Unveiling Revelation: The Spirit-Paraclete and Apocalyptic Disclosure in the Gospel of John

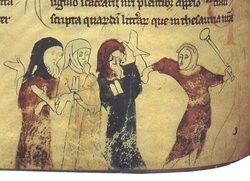

- Christopher Rowland, 'Intimations of Apocalyptic': The Perspective of the History of Interpretation

- April DeConick, Why are the Heavens Closed? The Johannine Revelation of the Father

- Jutta Leonhardt-Balzer, The Ruler of the World, Antichrists and Pseudo-Prophets: Johannine Variations on an Apocalyptic Motif

- Loren Stuckenbruck, Evil in Johannine and Apocalyptic Perspective: Petition for Protection in John 17

- Judith Lieu, Text and Authority in John and Apocalyptic

- Robert G. Hall, The Reader as Apocalyptist in the Gospel of John

- Robin Griffith-Jones, Apocalyptic Mystagogy: Rebirth-from-above in the Reception of John's Gospel

- Adela Yarbro Collins, Epilogue