Forbidden Gospels Blog

If you subscribe, my new posts will automatically be sent to you.

Apocryphote of the Day: 7-18-08

/Treatise on the Resurrection 49.9-25 (second century Valentinian text)

Commentary: I moved the second sentence into first person ("we") instead of third person ("he") to have a gender inclusive reading. Here is a group of Christians who thought that in Christ they had already obtained the resurrection. Does their discussion seems to imply a more general Christian resurrection expectation at personal death (not just eschatological, on the last day)? I wonder.

Apocryphote of the Day: 7-16-08

/ Jesus said, "The Spirit draws all souls together and takes them to the place of light. Because of this, I have said to you, 'I have come to cast fire upon the earth.' That is, I have come to purify the sins of the whole world with fire."

Jesus said, "The Spirit draws all souls together and takes them to the place of light. Because of this, I have said to you, 'I have come to cast fire upon the earth.' That is, I have come to purify the sins of the whole world with fire."Pistis Sophia 4.141 (fourth century Gnostic handbook, a relic of a new religious movement that we can call 'Gnosticism')

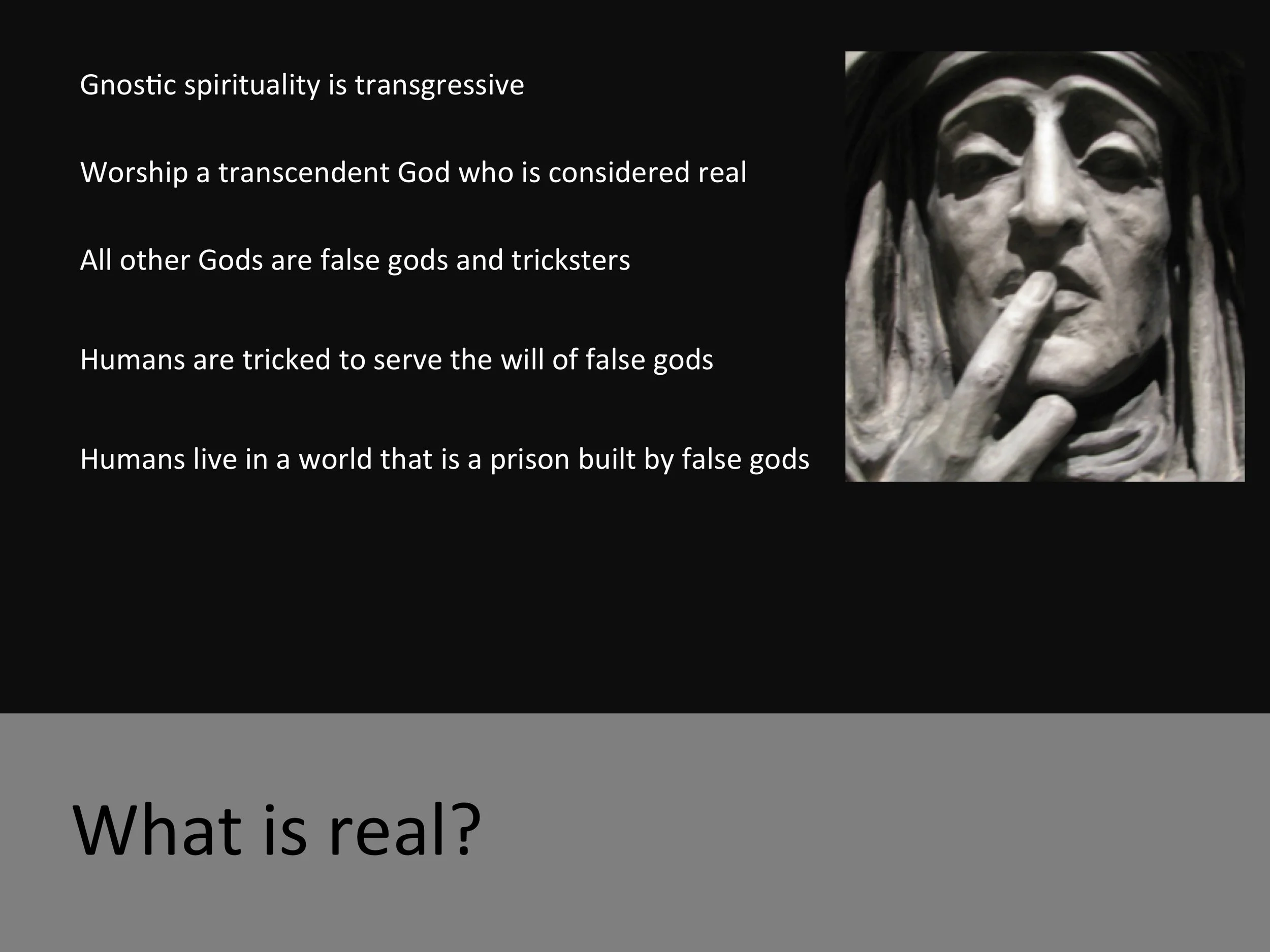

Commentary: Here we see the Gnostic reliance on the Platonic doctrine of the immortality of the soul. In order for the souls to be able to return to the origin, according to Platonic teaching, they must be freed from the passions, lust, greed, evil. So Jesus functions by removing the sins from the souls through some kind of communal cleansing which was done when he came to earth and cast fire upon it.

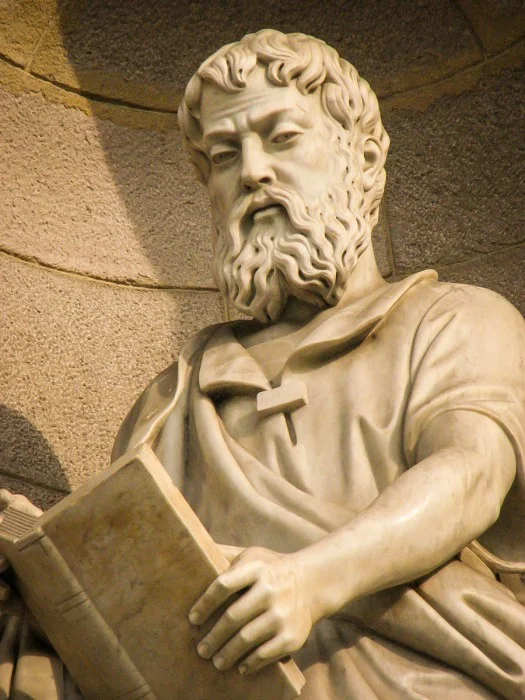

Sculpture is from Orvieto Cathedral, fourth pillar, Last Judgment. This scene depicts the resurrection from the dead. Lorenzo Maitani 1310-1330 CE.

Apocryphote of the Day: 7-15-08

/ "The resurrection of the souls of the dead takes place even now in the time of death. But the resurrection of the bodies will take place in that (last) day."

"The resurrection of the souls of the dead takes place even now in the time of death. But the resurrection of the bodies will take place in that (last) day."Macarius, Homily 36.1 (Syrian father from fourth century)

Commentary: this quotation represents the problem that one faces when the Jewish concept of bodily resurrection (that is, the resurrection of the whole person) encounters the dualistic Platonic anthropology (that is, the soul and body). Pagans believed in the immortality of the soul, that it could be released to return to its divine origins at death if the person had been pious. So what benefit was Jesus' death, the pagans asked? Part of that answer appears to be that Jesus' body was restored, and so will yours if you become Christian. Eventually the type of view develops that Macarius suggests: that at personal death, the soul journeys onward, and at the last day the body will follow.

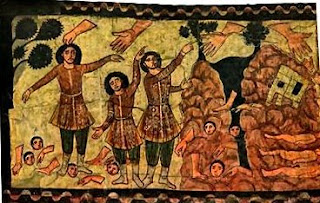

The illustration depicts Ezekiel 37, 3rd-century fresco, Dura Europas synagogue in Syria.

Hosea 6:1-3 and the Apocalypse of Gabriel

/

Although I remain skeptical about the authenticity of the Apocalypse of Gabriel because we do not know its provenance, and ink on stone for a literary text seems odd, I am very curious about the three day resurrection reference found on the stone.

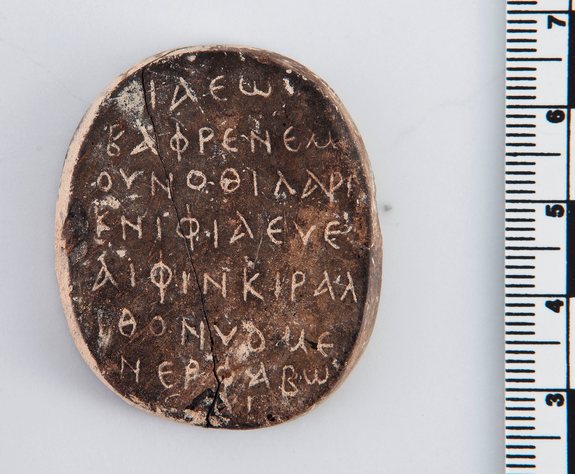

The stone tablet and its owner, David Jeselsohn

There is a hymn embedded in Hosea (6:1-3) that has relevance to this discussion:

Come, let us return to Yahweh,Originally this priestly (?) poem from 8th c. BCE or earlier, addresses Israel's expectations that the nation has become ill but that God will heal it in as shortest time as possible. It was similar in content with the priestly psalms in which the wounded are raised up from their sickbeds (cf. Ps. 41:3, 10) and statements that God wounds and heals, kills and enlivens (Deut. 23:39; Ezek. 30:21; Job 5:18). In this old context, it had nothing to do with resurrection from the dead.

for he has torn, and he will heal us;

he has stricken, and he will bind us up,

will preserve our life.

After two days, on the third day

he will raise us up, that we may

live in his presence.

Let us know, yes, let us strive,

to know Yahweh.

As the dawn (breaks, so) certain is

his going forth.

He comes to us as surely as the rain,

as the spring rain that waters the land.

However, once resurrection doctrines came into existence in the Maccabean period, could Hosea 6:1-3 have been read as a post-mortem expectation, that the dead would be raised by God on the third day after their deaths? Could the Christians have understood or framed Jesus' resurrection along these expectations?

The earliest blatant reference to this is made by Tertullian (Against Marcion 4.43.1ff.; An Answer to the Jews 13.23). There is an old scholarly article written on the scriptural basis for the three day expectation in the Journal of Biblical Literature 48 (1929) pp. 124-137, by S.V. McCarland, "The Scripture Basis of 'On the Third Day.'"

So it is quite possible, that in Judaism at the time of Jesus there was an expectation that after death, God would resurrect those who died "on the third day" after they had died, using Hosea 6:1-3 as the proof-text. I can imagine the first Christian Jews relying on this expectation as they told stories about Jesus' resurrection. This expectation happened to get connected with Messianic beliefs through association with the Jesus stories.

But what the Apocalypse of Gabriel suggests, if it is authentic and should be read in the way that Knobl insists, is that in Judaism there was also the expectation that the MESSIAH would die and be raised on the third day. Again, I am very hesitant about this since so much of the early Christian literature is open apology for the Messiah's death (and suffering and resurrection) which Jews apparently did not expect. I'm not sure how to reconcile this with the Apocalypse of Gabriel.

Part 5: Bodily resurrection and sematics

/Chad says:

At the risk of reheating a now cooled debate and perhaps further riling your confessional Christian interlocutors, who continue to grasp at straws with appeals to philosophy of science, definitions of inductive reasoning, and the like (all, by the way, standard and now tiresome postmodern apologetic tactics) in their defense of bodily resurrection as a "unique" event, I wish to call attention to a more fundamental issue in any discussion of the “resurrection” of Jesus - the arguably problematic modern semantic range of this English word.

As the Greek readers in your audience should know, this word stems (via Latin resuscitāre and resurgere) from two Greek verbs: anistēmi and egeirō (cf. Hebrew qum). From these well-attested verbs in LXX and GNT, we derive the notions of “stand up,” “rise,” “raise up,” “rouse,” “restore,” “set up,” or even “awake” (each usually in the quite mundane sense of things). Of course, such prosaic usages would doubtless have also been imbued with other symbolic meanings. However, I doubt that many Christian commentators - both those with and those without control of ancient Greek - have really pondered these words and their import apart from the KJV-influenced semantic range or even from a non-Christian (modern and/or ancient) perspective. Moreover, I doubt that, in the case of, say, the Corinthians (i.e., “pagans”) and their disdain for a resuscitated corpse, many commentators even consider that folks in antiquity could misunderstand the meanings or semantic range of words (theologically tinged or not) – just as folks do today. This latter point in general is rarely mentioned in studies of Paul or Christian Origins. In fact, the notion of misunderstanding in this sense, it seems to me, must be taken into account in any responsible study (whether confessional or secular) of, say, the so-called “Gentile Mission” or really any first-century dissemination of the Christian “gospel” and its subtleties to those without a “Jewish” or “Christian” mindset. (Anecdotally, I cannot help but think – in a more trivial sense – of "The Life of Brian" with its “Blessed are the Cheesemakers.”) But seriously, it is likely that across the Greco-Roman world the Greek verbs anistēmi and egeirō (and their derivatives) were not wholly refined in the “Christian” sense, but were largely culturally refined. Perhaps, then, some of what we witness in Paul’s Corinthian correspondence, for example, is just as much a rhetorical struggle over the “meaning” of the word egeirō(cf. 1 Cor.15:4, 20) as a presentation and reiteration of Pauline “theology.”

Now I am not arguing that anistēmi and egeirō did not or could not signal bodily “resurrection” in the modern Christian sense in the first century. I simply call attention to an issue that is certainly under-discussed, and an issue that would fit well with your suggestion about rethinking the problem of “ante-eschaton” resurrection in first-century Judaism.

Finally I submit that, as much as it may pain some Christians and Christian scholars to do so, the polysemy of “resurrection” in ancient usage must be factored into any modern reconstruction of Jesus’ supposed postmortem appearances.

Part 4: Have we decided anything about the resurrection?

/1. I am reaffirmed (thanks to an anonymous blogger named "John") that I should stick with SBL (smile!). I think he is right when he says:

I think you would grow tired, eventually, of the relative monotony of the AAR crowd, careful as that crowd is to rule out of consideration the possibility that God in the classical Jewish or Christian sense exists, while ruling in every imaginable modern ideology as a platform from which to interpret religious texts. I can't imagine you disagreeing that many AAR papers (I've heard or read many myself) are little more than sermons which preach to a choir of choice...2. Mr. Walters has written many fiery comments in all the resurrection posts, and says that my position is nonsense and that I have misunderstood his. Certainly I do not consider my position that "dead bodies stay dead" nonsense. We can argue many things are possible, and that there are no absolute conditions for laws of nature. Tomorrow I might wake up to find myself green, or the floor no longer solid, or dead bodies rising out of the tombs. But I doubt that that will be the case tomorrow or the next day or any day of my life. Mr. Walters is correct that an inductive argument does not lead to a logically necessary conclusion. But the point of making arguments from history is that they are very strong inductive arguments. The argument that Jesus wasn't physically resurrected from the grave is a very strong inductive argument, much stronger in my opinion than the opposite - If anything is possible, Jesus could have risen from the grave, because we can't say based on inductive reasoning that on one can rise from the grave. On this point, I would like to quote from one of Wade's books by Simon Altmann (Is Nature Supernatural? p. 55-56):

I must remark for the moment that the question of the use of induction in scientific practice remains one of our major problems. I shall later propose a solution based on the principle that propositions in science never stand or fall on their own; that they must be closely knitted within what I shall call the scientific mesh of facts and theories, and that the use of induction for a proposition can only be legitimized when the proposition is integrated (or, as I shall call it, entrenched) as part of this scientific mesh.It is my opinion that Altmann's "solution" is the one that historians should (even must) own as their own. Without it, we cannot "do" history, as we cannot "do" science.

3. Deane has a wonderful response to my thoughts that just maybe there were some Jews around the time of Jesus who toyed with the idea that some of the righteous dead had already been resurrected. Yes, this would have quite the implications for christology, if it is so (which I'm still pondering). I had always assumed that the righteous dead were "spirits" living with God before the end-of-the-world - Loren is correct that there is a difference between immortality of the soul and a resurrected body (Alan Segal has made this very clear in his wonderful book, Life After Death) - but the teaching attributed to Jesus is not making this argument. He is arguing that the resurrection of the dead is proven because Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob live with God already.

4. Leon has pointed to a couple of OT stories that he thinks could be understood in terms of resurrected bodies. First to note - the stories probably did not refer to resurrection "originally." But what they may have come to mean to Jews in the first century is another story altogether. My question is this: Are bodies brought back from death the same as resurrected bodies in first century Judaism? Maybe. On this point I think of the story of Jesus bringing Lazarus back from the grave and John's understanding of this in terms of resurrection: "I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live..." (11:25). If Lazarus is the beloved disciple in John (and I think he is the only good choice narratologically), then the Johannine Christians thought that Lazarus had been resurrected from the dead and thus would never die. So they were surprised and traumatized when he died (John 21). I guess what I'm saying is that whoever wrote John believed that the raising of Lazarus was his resurrection.

5. I think that naturalistic explanations can explain the story about Jesus' physical resurrection. I have thought for a long time as James Crossley has indicated, that we should be investigating these sorts of explanations. James writes in the comments:

I find myself more and more coming to the same kinds of conclusions on the issue of historical practice. There are *always* plenty of alternatives to supernatural explanations. Consequently, it becomes futile to try and explain things with reference to supernatural which can hardly be measured or analysed in a meaningful (in terms of historical reconstruction) way.For me this would be emphasizing religious experience, psychology, dream states, construction of memories within an eschatological Jewish community, transmission of stories in oral-literate environment, and so forth.

Part 3: A lack of precedent for Jesus' resurrection?

/He writes:

What the disciples believed to have happened should be the crucial question for historians. What actually happened (or did not happen, as the case may be) may be of more burning interest to theologians and scientists.On this point I would like to raise a very interesting passage from the Synoptics. It so happens that this is one of the passages I am writing for the commentary that members of the NT Mysticism Project are collaboratively putting together. It is Matthew 22:23-32. I had volunteered for the passage because of my past work on encratic behavior and the rejection of marriage by many early Christians, and I never expected to come face-to-face with an odd passage about the resurrection. This is a passage I've read a thousand times, but for some reason, when I began working on the logic of the whole pericope, I found that Jesus appears to be arguing for the feasibility of the resurrection because Abraham, Issac and Jacob were resurrected already. Thus Jesus says in Matthew 22:31-32 that the resurrection is proven because scripture says that God IS (not WAS) the God of Abraham, Issac and Jacob, he IS the God of the living, not the dead.

But Wright is a theologian as much as a historian, as we all know. It's always amazed me how he thinks the lack of precedent for Jesus' resurrection historically validates it. I.e. That since Jewish tradition didn't provide for an individual's resurrection before the end -- especially for a messiah who had gone down in shame -- the Christians wouldn't have made such a far-fetched claim, unless it were actually true. (emphasis mine)

This same thread is picked up in another story attributed to Jesus (Luke 16:19-31). It is that famous story about the poor man Lazarus who, when he died, was carried away by the angels to be with Abraham. A rich man also dies but goes to the torments of Hades. He looks up and sees Abraham far away with Lazarus at his side. He begs Abraham to send Lazarus to his family to warn them about the place of torment. Abraham tells him that they already know this - they have Moses and the Prophets and should listen to them. Besides he argues, "If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead." Not only do we have here the belief again that Abraham wasn't dead (whether he was resurrected or a spirit is not clear in this passage), but we have a Jewish man who believes it possible for a dead person to rise and go to talk to his family - and this is NOT the general resurrection of the dead at the end of time.

At any rate, I am wondering now about our common assumption that Jews in this time period thought that the resurrection was only an end-of-time event.

Part 2: Can "A" Dead Body be Raised?

/Here is Mr. Walters' comment:

I hope that appeal to biology was not meant to be taken seriously. The facts of biology are based on repeatable events and inferences from statistical data. By definition a unique event like a resurrection does not fall under the biological paradigm. Repeated experience with 'dead bodies staying dead' might produce a strong mental aversion to the idea of a resurrection (as Wright points out, this held for the ancients as much as modern people; ancients knew that when people died, their bodies were just corpses), but it means nothing one way or the other about whether such a thing is possible, which will depend on what one thinks is the ultimate explanation for the existence of the universe.By definition? The irreversibility of death means nothing? The historicity of the physical resurrection of Jesus simply depends on one's view of the universe?

The more I think about these types of "arguments" (if we can even use such a word for them), the more concerned I become. If the field of biblical studies has been reduced to this, then it is not worthy to be part of the Academy.

For a long time I have resisted the separation of AAR and SBL on grounds that the biblical field is a historical field of study. I have worked for years in the Society, creating and chairing both the section on Early Jewish and Christian Mysticism and the seminar called the NT Mysticism Project. Year in and year out I have given papers in many venues, published with SBL press, been a spokesperson for the Society whenever in conversation with AAR scholars. But comments and nonsense like this are making me reevaluate that stance. Perhaps the AAR folks are right in separating from the SBL, in their insistence that all we will ever be are caretakers of the church rather than critics of religion.

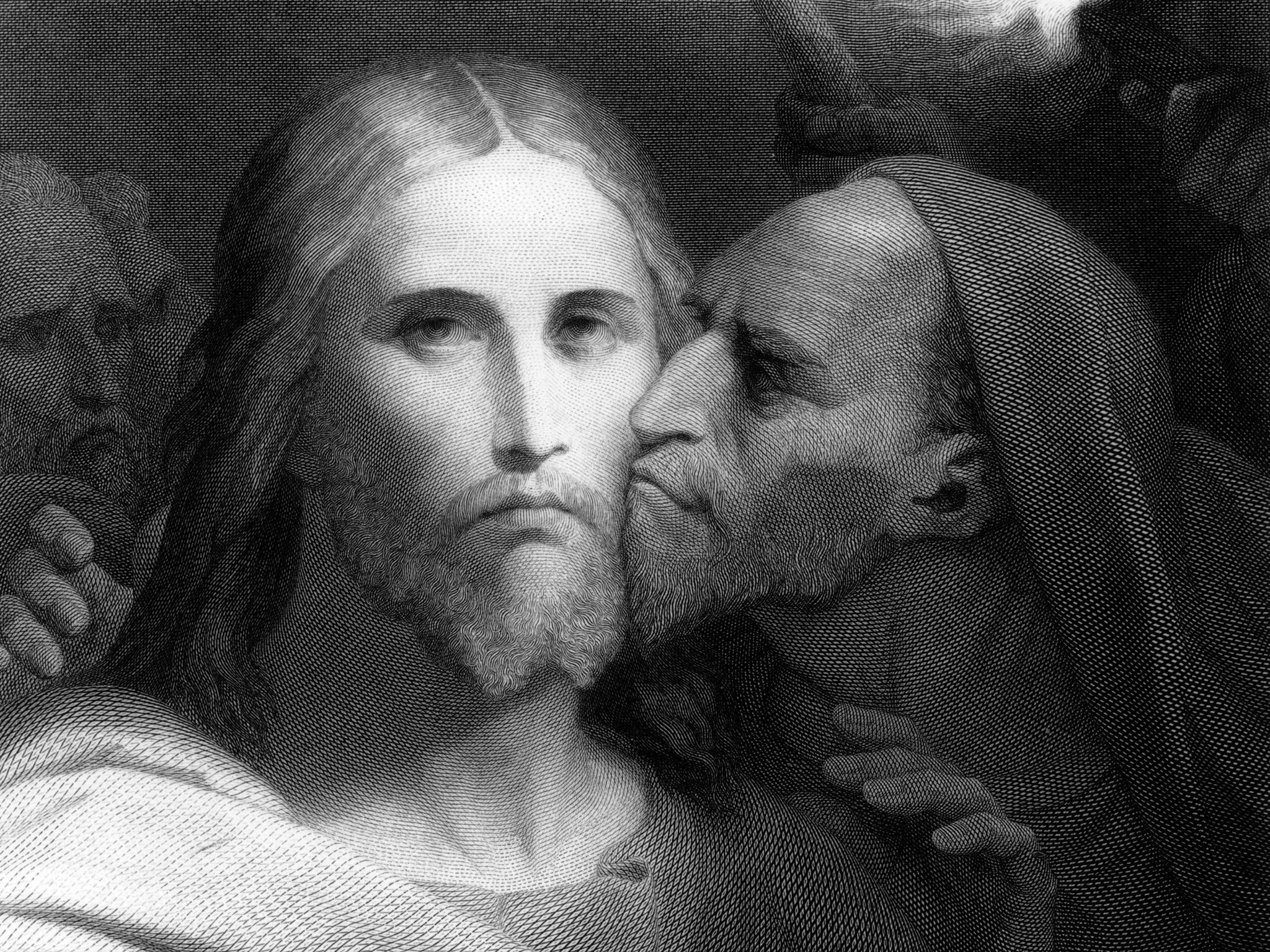

Part 1: Did the Resurrection Happen?

/For what my two cents might be worth on this topic, I insist that whether or not the resurrection actually happened, is not a question that needs to concern historians for several reasons.

1. Because of biology. Dead bodies remain dead. They are not physically brought back from the dead after three days, two days, one day, or otherwise. It is a theological argument to say otherwise, and it can never be made into anything other than a theological argument.

2. If a historian studying any other person than Jesus made the claim that such-and-such person came back from the dead, what would we think of that historian? Especially if the reason to believe such a claim was because many people say they witnessed it and were willing to die for it? How many people are willing to die for things they think have happened, are happening, or will happen? This doesn't mean they have happened, are happening, or will happen. It means that human beings believe all kinds of things that didn't or can't happen, even to the point of dying for that belief. This is a psychological issue, not a historical one. By the way, in case we should forget, there were a lot of Christians who were not willing to die for their beliefs and opposed those who did.

3. I think we are asking the wrong question, and getting bogged down (yet again) in theology. What matters for the historical study of early Christianity is that the early Christians thought/believed/promoted/remembered/taught that Jesus had risen, not whether it "really" happened. It is the belief that is foundational to understand the early Christian movement. It tells us that it was an apocalyptic movement with strong eschatological factors, including the belief that Jesus' resurrection had begun the events of the last days - he had inaugurated the general resurrection (i.e. Matthew's wonderful story of the holy men and women in Jerusalem, and Paul's comment that he was the "first" to rise).

In other words, if we grant that "something" happened, that some of the early Christians experienced something, they went on to interpret it according to their Jewish expectations and traditions at hand. If we don't grant this, then we have to say they made it up, which I am less likely to think given what I have studied about religious experiences and the hermeneutical processes that follow such experiences. I continue to make detailed studies of human memory - both individual and collective - as well as the processes by which stories are created and spread within an environment dominated by an oral consciousness. All of this scientific data - if studied without theological blinders - supports the fact that stories and memories about things does not mean that the thing as it is told or interpreted actually happened the way it was told or interpreted (or happened at all)!

4. If some early Christians experienced something (after-death dream? visions? or some other naturalistic possibility?), what it meant was NOT immediately the same for all of them. Not all of them thought it was a physical-material body that they encountered. Luke tells us that some thought it was a ghost, but not him - Luke has Jesus eat a piece of fish to prove Luke's own belief in the physicality of Jesus' resurrection and to polemicize against the ghost interpretation. John does not tell us that it was a physical body, at least not the same one Jesus had before his death. It may have had some corporeality (which spiritual bodies were thought to have - see Tertullian on this), but it was also a body that could walk through walls! Paul opts for a spiritual body, not a material one, as the resurrected body, a point that later Christian Gnostics like the Valentinians point out and develop. The fleshly interpretation is one that eventually came to dominate and win the day, but it took almost two centuries for that to happen.