Jew or Christian?

/1. Jared said:

This should not deny, however, 1) local variations and 2) temporal variations in the Second Temple Period, even as they revolve around some core issues of Temple, Torah, exclusive worship of YHWH, etc.Absolutely. This is one of those "givens" for me. I'm glad that Jared articulated it. I had a paragraph written to this effect, but deleted it before I posted the last entry because I felt that it was getting too long-winded.

2. Rebecca said:

I agree with those who argue that the parting of the ways was only a very gradual process (Annette Reed's book on the Fallen Angels brilliantly discusses this issue among others) - but that doesn't mean that Judaism didn't exist until the third century. To say that there is a continuum does not mean the phenomenon under discussion doesn't exist.This is an absolutely essential point that many people unfortunately seem to miss. I hope Rebecca plans to publish something on this.

3. Deane said:

More to the topic of conversation--and it is an interesting one, too. I really think that the debate about the self-understanding of first-century Israelites (which is, I think, the concern of the debate) are very much more close in viewpoint to your own wider positions, than those of their opponents. In Annette Yoshiko Reed and Adam H. Becker’s collection (The Ways that Never Parted), the writers show how the assumptions underlying the early “Parting of the Ways” model, which posited a definitive break between Christianity and Judaism from the first or second century AD, cannot now be sustained.I want to make something clear which I think is fuzzy. Long before Reed and Becker put out this collection, my doktorvater Jarl Fossum and my adopted doktorvater Alan Segal argued that Christianity was a Jewish movement long after the first century. I have been a loud advocate for this position myself both in my writing and in my classroom. You will always hear me talk about the NT literature as Jewish literature. I am not arguing that Christianity or Judaism in the first century or the second century were not multiform. Nor am I of the opinion that Christianity quickly became distinct from Judaism.

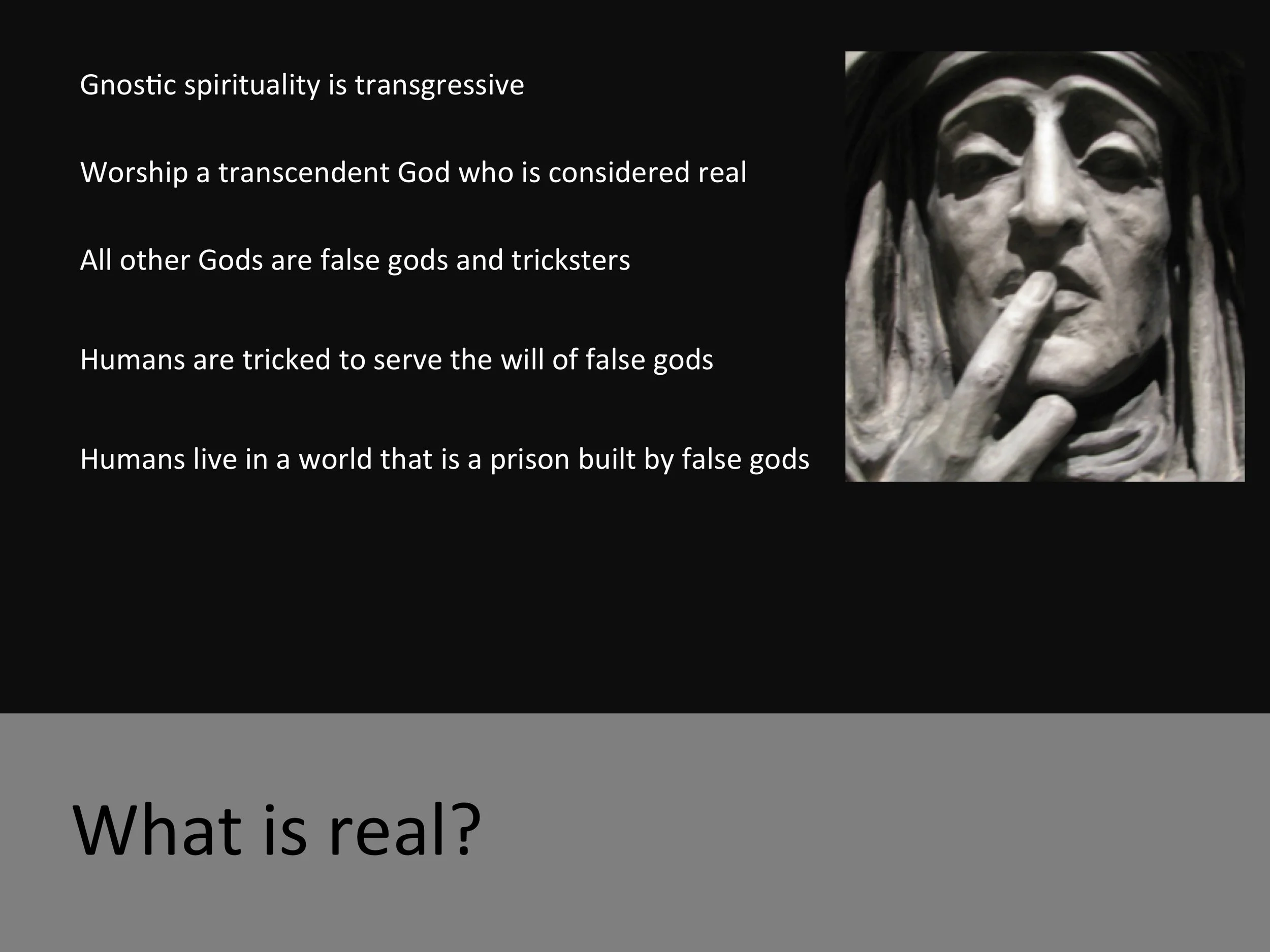

Now, having said this, at the same time I do not sustain the opinion that there was no separation between Judaism and Christianity in the first century. The creation of two separate religions from one was gradual, but it happened at different "moments" for different communities of believers within the traditions. For instance, for communities dominated by Gentiles, this separation happened more quickly than it did for communities maintaining their Jewishness. It also happened for different reasons, as complex as they are, including social identity formation alongside the most argued reasons which are usually christological or torah-related or the framing of orthodoxy.

As for the model of Boyarin, Reed, and Becker, who argue for a very late separation (if any at all), this model is not embraced by all nor has it become standard. If you haven't had a chance to read Giorgio Jossa's work yet, I highly recommend it. His important Italian book on this subject has just been translated into English: Jews or Christians?. He puts the brakes on all of this, and reassesses how the arguments for pluriformity are being (mis) used. He takes us back to Paul and the gospels, and asks us to look again from the perspective of a sociologist. Although I quibble with him over various interpretative points, I truly appreciate his candor and his willingness to reassess the current trends in biblical scholarship. Most interesting is his last chapter on Roman perspectives of Jews and Christians, and how early (60s) that they began making clear distinctions between these groups, treating them very differently from each other.

Enough for today. Must get to my writing.